- Home

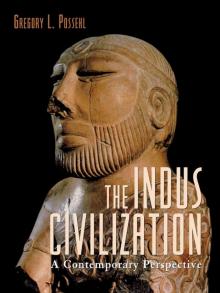

- Gregory L. Possehl

The Indus Civilization Page 15

The Indus Civilization Read online

Page 15

Chanhu-daro is one of the best-known settlements of the Indus Civilization. Today it is a group of three low mounds that excavation has shown were parts of a single settlement estimated to have been approximately 5 hectares in size (about the same size as Lothal; see figure 3.13).

Chanhu-daro was excavated by Majumdar in March 193057 and again during the winter field season of 1935—1936 by Mackay.58 The latter’s excavations show that the occupation of Chanhu-daro was divided into four periods, with four occupational sublevels within the Mature Harappan (table 3.6).

Table 3.6 Periods of occupation at Chanhu-daro

Period IV Jhangar (Late Bronze Age?)

Period III Trihni

Period II Jhukar (Posturban Harappan)

Period I A—D Mature Harappan

The Indus occupation had buildings of baked brick, paved bathrooms, and a civic drainage system that “was as well thought out and doubtless quite as effective as that of the larger city (Mohenjo-daro).”59 Some buildings were grouped along a wide street that ran northwest to southeast but was cut by at least one thoroughfare coming in at a right angle. This attention to town planning was not seen in the uppermost Indus levels.

A bead factory and furnace are the most interesting features of this occupation.60 The center piece of the installation was a furnace that was used in several ways, including the glazing of steatite, providing heat to bring out the red color of carnelian, and preparing stone for better chipping, also a part of the bead-making process (figure 3.14).

There are two copper—bronze toy vehicles from Chanhu-daro. 61 The human figurines are very much like those at Mohenjo-daro; however, the very elaborate females are not present. One interesting male figurine has a very close parallel from Nippur.62 Chanhu-daro seems to have a larger number of bird figurines than other Mature Harappan sites. Perhaps the most interesting figurines are the bulls with single horns, true unicorns.63

Little is known of the upper periods at Chanhu-daro, and the exact relationship between the important Jhukar levels and the Mature Harappan has not yet been settled. Of Trihni and Jhangar almost nothing is known, and further exploration of these periods is a pressing problem in the regional archaeology of Sindh.

During Mature Harappan times, Chanhu-daro seems to have been a regional craft center for the Sindhi Harappans. This is seen in the bead- and seal-making area and was also confirmed by intensive surface exploration that found concentrations of pottery wasters, debris from the making of chalcedony/carnelian beads, faience work, and shell working.64 These are much the same kinds of materials and craft activities that are found at Lothal 250 kilometers to the southeast, and one would suspect that there was an intimate connection between these two sites during the period of the Indus Civilization.

Kalibangan

Kalibangan, also known as Kala Vangu and Pilibangan, is another of the well-known Indus settlements. It is a two-period site, with a Sothi-Siswal and Mature Harappan occupation. The site is situated on the southern escarpment of the Sarasvati, near its confluence with the Drishadvati. The ASI undertook excavation there for nine seasons beginning in 1960—1961 and ending in 1968—1969 (figure 3.15).65

The Sothi-Siswal settlement is surrounded by a wall approximately 250 by 170 meters in extent. The first phase of the wall was made of mud bricks laid to a thickness of approximately 1.90 meters. A second phase of construction brought the thickness of this wall up to 3 or 4 meters, varying from place to place. The inner and outer faces of the “fortifications” were plastered with mud. Only one entrance, at the northwest corner, was excavated; other entrances were probably obscured by later Harappans.

Direct evidence for cultivation was found in the form of a preserved plowed field, about 100 meters to the south of the Period I settlement. It was covered by slump from the Sothi-Siswal occupation and consisted of alternating furrows and hummocks in the earth. These were oriented to the cardinal directions and have a close ethnographic parallel in modern Rajasthani agricultural practice.66

When the Indus peoples reoccupied Kalibangan, their ceramics included many of the shapes and fabrics of the Period I occupation. This lasted for about one-half of Period II, when it gave way to a more purely Indus ceramic corpus.67 Other sites in the northeastern region of the Indus Civilization share this mixture of ceramics as seen at Kalibangan. The Mature Harappan plan of Kalibangan is significantly different from the original. There are two parts: the High Mound (KLB-1) to the west, covering most of the abandoned Early Harappan settlement; and to the east is the Lower Town (KLB-2), most of which is on virgin soil. The old entrance in the northwestern corner of the High Mound was once again used.

Figure 3.13 Plan of Chanhu-daro (after Mackay 1942)

Figure 3.14 The furnace in the bead factory at Chanhu-daro (after Mackay 1942)

During Period II, the High Mound was well fortified, although the southern half was stronger than the north. The southern half of the High Mound was equipped during Indus times with a series of mud-brick platforms on which “ritual structures,” connected with the use of fire and possibly animal remains, were located. These have been called “fire altars.” They are oval in plan, sunk in the ground, and lined with mud plaster or bricks.

Most of the people lived in the Lower Town of Kalibangan. It was surrounded by a fortification wall ranging in thickness from 3.5 to 9 meters. The wall had three or four phases of construction, and it, like the High Mound, was plastered with mud and tapered from bottom to top. The fortifications protected the town, which was laid out in a gridiron plan, separating blocks of habitations. There were four streets running the full north-south distance of the settlement and three (possibly four) oriented east-west. It is interesting that the north-south streets do not run parallel to the fortifications, and two of them converge on the principal entrance to the Lower Town in the northwest corner of the settlement. The brickwork tells us that buildings at some intersections seem to have been equipped with wooden fenders to limit damage to, and done by, vehicular traffic. There is some indication of habitation extending outside the fortifications in the protected area to the south of the High Mound and to the west of the Lower Town.

A significant number of Indus stamp seals and sealings were found at Kalibangan, including examples of both unicorn and zebu motifs. A cylinder seal is of particular note (figure 3.16).

There is a small mound about 75 meters to the east of the Lower Town at Kalibangan. This has been designated KLB-3 and is called a “ritual structure.” Excavation exposed a mud-brick structure enclosing fire altars much like the ones on the High Mound at the site.

A cemetery is located about 300 meters west-southwest of the habitation area.68 This is both downwind and downriver from the settlement itself. There are three types of burials at Kalibangan, and they can all be assigned to the Mature Harappan:

Typical Harappan extended inhumation in a rectangular or oval pit

Pot burials in circular pits, but without skeletons

Cenotaphs in the form of pottery grave goods in pits but without skeletal material

Figure 3.15 Plan of Kalibangan (after Thapar 1975)

Kalibangan is one of the few Mature Harappan sites with a true double-mound layout, as at Mohenjo-daro. It is strategically located at the confluence of the Sarasvati and Drishadvati Rivers and must have played a major role as a way station and monitor of the overland communications of the Harappan peoples.

Kulli

Kulli is a mound of about 11 hectares at the eastern end of the Kolwa Valley in southern Baluchistan. The mound rises 9 meters above the valley floor. Sir Aurel Stein conducted a small excavation at Kulli during his 1927-1928 exploration of Gedrosia.69 There are no radiocarbon dates for this site, but dates from other sites with Kulli remains (Nindowari and Niai Buthi) indicate that it was contemporary with the Indus Civilization. This dating is sustained by similarities in Kulli material to that of the Mature Harappan (figure 3.17).

Figure 3.16 Impression of the Kalibangan cylinder seal (after Thapar 1975)

>

Figure 3.17 Plan of Kulli (after Stein 1931)

Kulli and the Indus Civilization

Kulli pottery includes many vessel forms identical to those of the Indus Civilization: dishes on stands, “graters,” some jars, and large storage vessels. There is also a great deal of purely Mature Harappan plain red ware on Kulli sites. However, the Kulli painting style, especially with the wide-eyed animals and fish motifs, is distinctive (figure 3.18). This figure contains some Mature Harappan—like pots from Kulli’s sister site, Mehi.

Nindowari is also a very large site with monumental architecture and Harappan unicorn seals.70 The geographic juxtaposition of the Kulli and Sindhi Domains, with ecological complementarity and these cultural dimensions, leads to the conclusion that the Kulli complex represents the highland expression of the Harappan Civilization.

Figure 3.18 Kulli-style pottery (after Stein 1931) 71

Sutkagen-dor

The westernmost Indus site is Sutkagen-dor, located in the Dasht Valley of the Makran (figure 3.19). It is near the western bank of the Dasht and its confluence with a smaller stream, known as the Gajo Kaur. This is 42 kilometers from the sea along the Dasht River route. Sutkagen-dor was discovered in 1875 by Major E. Mockler, who conducted a small excavation there. As a part of his Gedrosia tour, Stein came in 1928 and conducted a small excavation.72 Dales was at Sutkagen-dor from October 7 through 20, 1960, as a part of his Makran survey.73

Figure 3.19 Reconstruction of Sutkagen-dor (after Dales and Lippo 1992)

Sutkagen-dor measures approximately 300 by 150 meters, or 4.5 hectares. Stein found structures outside the northern wall of the enclosure, and there are other remains on the eastern side of the site, possibly only to the north. He found “cinerary deposits . . . one above the other. . . . The uppermost deposit proved to consist of two pots, one stuck in the other.”74

Dales unearthed a structure built against the western fortification wall. This was made of both stone and mud bricks, some of the latter being rather large (50 centimeters long) and made without straw. A trench across the eastern fortification wall demonstrated that the inner face of the wall was vertical. It is estimated that the outer wall at this point would have been about 7.5 meters thick at the base.75

Stein noted the high number of flint blades, 127 of them, up to 27.5 centimeters long, but no cores.76 Stone vessels—one fine example in alabaster—were found. Arrowheads in both chipped stone and copper-bronze were also found. The copper-bronze examples have good parallels at Mohenjo-daro.77 Stein also noted the abundance of worked-shell and a fine onyx bead. The Dales excavations recovered a complete copper-bronze disk of the type found at Mehi and probably associated with the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC).

The pottery is typical Indus red ware in the usual shapes, including the dish-on-stand and black-on-red painted ware. Dales and Lipo note the absence of square stamp seals of Mature Harappan type along with figurines, beads, faience, and clay balls.78

Sutkagen-dor is a more or less pure Sindhi Harappan site in the Kulli Domain. There is no Kulli pottery mentioned in the reports on the site. It was not a port, since it is so far from the sea. Still, the place may have played a role in commerce between the Indus Civilization and the west, but further work at the site is needed to demonstrate this.

Lothal

The ancient site of Lothal was a town of the Indus Civilization. The name could be interpreted to mean “Mound of the Dead Men,” the same as Mohenjo-daro. Lothal was discovered by S. R. Rao of the ASI in 1954. He excavated there from 1954-1955 to 1959-1960 and in 1961-1962, 1962-1963.79 Lothal is located near the head of the Gulf of Cambay in Gujarat, in the southeastern part of the Indus Civilization that would have been a frontier with peninsular India. Lothal is the southernmost of the Sindhi Harappan settlements (figure 3.20).

Lothal A, the first occupation, dates the Mature Harappan. The second occupation, designated Lothal B, is Posturban, circa 1900-1750 B.C. During the Mature Harappan, the settlement was about 4.2 hectares in size, not counting the area of the baked-brick-lined enclosure. The site was much smaller in Lothal B times.

Rao has claimed that Lothal was a port town of the Indus Civilization, a seat of maritime commerce linking ancient India with Mesopotamia. Some scholars propose that the large, brick-lined enclosure on the eastern side of the settlement was a dockyard or harbor for ships involved in commerce, but this has been disputed by others, including Thor Heyerdahl.80 Most archaeologists feel that this enclosure was an ordinary tank for the storage of water.

The settlement was divided into three districts: an acropolis, a lower town, and the brick-lined enclosure. On the summit of the elevated mound is a building identified as a warehouse, as well as a long building with bathing fa-cilities and other structures of baked brick, a striking feature of Indus architecture. The elevated portion of the site was also provided with a baked-brick-lined well, a drain, and soak jars to take water from a building, the use of which has not been determined. These are all good Sindhi Harappan traits. To the north of this elevated platform were the domestic quarters of the town, with private houses. No formal market facilities have been documented. The western lower town was a manufacturing area, only a small part of which was excavated.

Figure 3.20 Plan of Lothal (after Rao 1973)

Lothal was a center of craftsmanship. The excavations uncovered finished products and waste materials from a wide range of natural resources: copper, bronze, gold, carnelian, jasper, rock crystal and other semiprecious stones, ivory, and shell. Many of these materials were associated with a bead-making shop similar to the installation at Chanhu-daro. The bead-making technology at Lothal, as documented by waste materials (beads broken in the process of manufacture and drills), is the same as that used at Mohenjo-daro, Mehrgarh, and Shahr-i Sokhta in Seistan.

Typical Indus seals and sealings were found at Lothal, most of which were the classic types. A number of more provincial glyptic objects were present as well. Perhaps the most important of these was a Dilmun-type seal, which was a surface find.81

The terra-cotta figurines of both humans and animals are simple, even crude, unlike those from Mohenjo-daro or Harappa. Fine examples were found of miniature animals (bull, hare, dog, and a bird-headed pin) probably cast by the lost wax process. The remainder of the material inventory includes typical Indus weights, triangular terra-cotta cakes, model terra-cotta carts, and baked bricks. Bun-shaped copper ingots have parallels in western Asia, but the metal implements are purely Indus in character.

A small cemetery to the northwest of the site contained a number of interments, twenty of which were opened.82 This important feature of Lothal is discussed later in this book along with the other human remains of the Indus Civilization.

Rojdi

Rojdi is another of the well-known settlements of the Indus Civilization. It is strategically situated in the geographical center of Saurashtra, on a bank of the Bhadar River. It is a regional center of the Indus Civilization, one of the Sorath Harappan places. The location must have been significant in ancient times, since the site is approximately equidistant from all the borders of Saurashtra. This sense of centrality is also reflected in its size: approximately 7.5 hectares. While this hardly compares to Mohenjo-daro or Dholavira, it is large for an Harappan site in Saurashtra. Rojdi was a stable settlement in the sense that it was continuously occupied from about 2500 B.C. to 1700 B.C.83

The site is a low, oval mound about 500 meters long and 150 meters wide, sitting above the river (figure 3.21). Careful examination of the river edge of the site and a study of the outer wall, or circumvallation, has shown that the ancient settlement was essentially the same size as the modern archaeological site. There has been little erosion by the river, and the circumvallation is a feature that accurately delimited the boundaries of the living settlement.

Figure 3.21 Plan of Rojdi (after Possehl and Raval 1989)

Builders in Stone

Two large excavation areas have been exposed

at Rojdi: the South Extension and the Main Mound (figures 3.22 and 3.23). There was also a systematic excavation at an outer gateway (figure 3.24) and at an isolated structure on the northern slope of the site (figure 3.25). All of this very finely preserved architecture can be dated to Rojdi C, early in the second millennium B.C.

The people of Rojdi built their homes and associated buildings on stone foundations, probably with mud walls above them. No bricks were found, baked or otherwise, in the excavations. No wells, bathing platforms, and the associated street drains, as found at such places as Lothal, Mohenjo-daro, and Harappa, were found either.

Figure 3.22 Reconstruction of a building complex on the South Extension at Rojdi (after Possehl and Raval 1989)

Rojdi Was Home to Farmers and Herders

The Rojdi excavation was geared to find out as much about the people of Rojdi as possible, so they took their subsistence system as another focus of investigation: the plants and animals that were used, the farming calendar, the place of pastoralism in the lives of these people. This part of the excavation strategy was generously rewarded with a huge collection of bones and paleobotanical remains.

The domesticated animals present were to be expected: cattle, water buffalo, sheep, goats, chickens. The ancient Rojdi folk were also hunters, and the wild ungulates of Saurashtra were part of their diet, including nilgai, sambar, chital, and black buck. There are also the remains of at least one elephant, a house cat, and the cuon, or dhole, a doglike animal. The animal that dominates the Rojdi faunal assemblage, and that of all other Sorath Harappan sites in this region, is the cow, the Indian zebu. Cattle were the most important animals to these people, and the people must have had large herds.

The Indus Civilization

The Indus Civilization